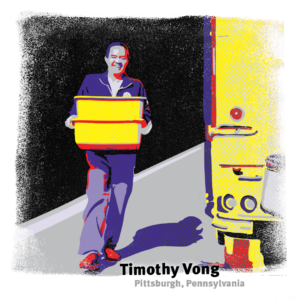

Timothy Vong

The journey to the United States for many immigrants is arduous. It may take months, losses, and thousands of miles to get to their destination. Their decision to leave their country is never an easy one, for it takes preparation and courage. Thai Gourmet Food Truck owner, Phoc Vong, or, Tim, as he is known to his customers in Pittsburgh, had a journey reminiscent of Castaway or Life of Pi, left floating in the merciless ocean, waiting for help that may never arrive. After fleeing the communists that took over Vietnam in the 1970s, Tim hopped from country to country, refugee camp to refugee camp, until he arrived in Pittsburgh in 1980. Today, he and his wife run this staple in the University of Pittsburgh community, serving a smile with every meal. “When I moved here, I thought I would get a degree, work in an office or travel, get a solid salary job or something. It didn’t turn out that way. But I ended up in the food industry and it is my passion. It is something I love and how I met my wife.”

Tim was 12 years old in 1980 when he arrived in the U.S.; beginning his new life in a country living with the effects of the Vietnam war, post-Civil Rights Act and an era of ambition and innovation. 1980s Pittsburgh had trolleys zipping down downtown streets where everyone went shopping. Big hair ruled the country and so did Reaganomics. According to Tim, it felt like he was the only immigrant around for miles. But even with that, all he ever felt was kindness, helpfulness, and warmth from his community and neighbors.

Tim was 12 years old in 1980 when he arrived in the U.S.; beginning his new life in a country living with the effects of the Vietnam war, post-Civil Rights Act and an era of ambition and innovation. 1980s Pittsburgh had trolleys zipping down downtown streets where everyone went shopping. Big hair ruled the country and so did Reaganomics. According to Tim, it felt like he was the only immigrant around for miles. But even with that, all he ever felt was kindness, helpfulness, and warmth from his community and neighbors.

Arriving in the U.S. not knowing any English proved difficult for Tim, his siblings, and parents. “My parents started me in sixth grade — I was supposed to be a little bit higher — but they said we have to change and adapt. We didn’t know a lot of people, so we could not communicate too much.” It took about six months before Tim felt he had a better command of the language, though his parents only knew enough to find a job. “They knew ABCs, just very common conversation, you know, ‘hello, how are you this morning? Good afternoon.’” But that alone was enough to begin their jobs in the food industry. His dad worked tirelessly as a dishwasher at a restaurant while his mom cut and prepped vegetables in the kitchen at a Chinese restaurant. “They worked six, seven days a week. 10 to 12 hour days. They tried to support us, pay the rent, put food on the table but it was very tough for them.”

At just 12 years old, Tim began to work to help his family stay afloat in the U.S. To this day, he remembers a man named George who managed newspaper deliveries in his area that gave him his first American job: a newspaper delivery boy, a quintessentially American job that began during the Great Depression. Waking up at sun’s first light to deliver papers before school was the norm. He’d go to school to excel at math and struggle with writing. He’d leave school and deliver his afternoon route of papers. He was a boy taking care of a household and called it “a blessing. I was able to make a little bit of money and I gave it to my mom and dad every time. Because my siblings are too young to do it. As a big brother, I had the responsibility for that.” Making sure his younger brother and sister did their homework, got fed, and took showers was part of his role and contribution in his family.

While this money helped, they were still struggling. Tim took a weekend job working as a busboy at 15 years old. He worked diligently and responsibly, getting a promotion to waiter, and then within three years, to a manager. “During that time, I learned about food — not just eating it — but I would ask questions to the chef sometimes, he give me tips about how to make things. It went into my memory and I go from there.” It was this decision to work in restaurants that eventually led him to work at a Cambodian restaurant, The Lemongrass Cafe, where he met his wife, Vilivan, who had worked in the Vietnamese food industry for many years. The food he serves to the University of Pittsburgh community is from nights with friends, exchanging recipes.

Timothy would love to one day go back and visit the country that has inspired so much of his cuisine, and which still holds powerful memories for him. “I still remember vividly when I was in Vietnam, in 1979 and there was a war.”Following the withdrawal of American troops in Vietnam in the mid-1970s, the Communist north then overtook the southern-located Bien Hoa, where Tim grew up. Daily life changed, income dropped dramatically, and Tim’s parents knew it was time to leave. They saved up money, traded it for gold bullion, and found a connection to get them on a fishing boat that would transport them to Malaysia. “A lot of people were on that fishing boat, it was shoulder-to-shoulder; packed in like sardines. We had to be hidden in the bottom layer of the boat because they don’t want to see people, they will be furious that we are trying to get out of the country.”

Tim, his siblings and parents waited until dark to find the captain of their voyage that would bring them to safety. After days getting thrown around the reckless ocean, they arrived in Malaysian waters, where the authorities forbade them from entering. Without enough food or fuel to continue to another country, they conspired of a way to let them in. “I remember the boat captain and the adults had a meeting saying, ‘let’s sabotage the fishing boat engine.’ So they purposely sabotaged the engine, Malaysia knowing we can’t go anywhere, hoping maybe they will sympathize and let us in temporarily.” Sure enough, they allowed them to temporarily stay on the coastline. The only obstacle was they would not transport them to the beach, so, they had to swim.

“I didn’t know how to swim. It came automatic. We just jumped in the water and tried to help my siblings. Too many people rushed into the water, it was like a protest. It was really bad.” Cold, wet, and scared, they arrive to shore where the authorities finally provided them food and water, outlining the terms of their stay. “One month and then you must leave.” After a month of reaching out to embassies and looking for sponsors to no avail, Malaysia couldn’t hold them anymore, sending them back into the ocean. With a new boat and fuel, food, and water to last these 70 people 3 days to live, they set off. “We were one little fishing boat going out deep in the ocean. Wide open ocean. We cannot see anything, we don’t know where we are. But we heard on the radio there was an Italian naval ship out somewhere. The chance of us finding them was a million to one. It was like the lottery.”

Their boat got knocked by waves and bigger waves, they were thrown from one side of the boat to the other as the ocean smacked them around. Tim was sure they were all going to die out there. They continue to go as far as the fuel would let them until the fourth day came and there was no more food, no more water, and no more fuel. The fishing boat was left floating aimlessly. Days passed and Tim remembers the sick and hungry getting worse. “I remember some elderly passed away. They just tossed them in the ocean.”

It was day five of no food or water. There was no more energy left to give from any of them; barely even able to keep their eyes open. Suddenly, there was a bright light — a spotlight shining on their boat. “I thought it was the sun. My mom and dad thought we died and went to heaven already because we knew we were going to die anyway in the ocean.” The light moves enough for them to see what was before them, “it looked like a GIANT building. It was a big ship, come to save us. It gave everybody energy, everybody’s eyes started opening. They started praying and kneeling down and saying THANK YOU.” It was the Italian naval ship they had heard of before they set off on this adventure. It felt like folklore at that point, holding on to salvation that may never come. It was the one in a million chance that came to save them. They won the lottery and lived.

The ship transported them to Italy where they lived in a refugee camp for nine months, with freedom to work, eat, and learn with others. From there, they set off to Pittsburgh.

“I am so happy to live in this country and have a better life. There are so many things you have the freedom to do to improve your life. As long as you put a lot of time and passion and work and just focus and be serious about what you do, then you have a chance to be better in life and pass it on from generation to generation.” To build generational wealth and prominence in this country has become a new American dream, one that motivates millions and a responsibility first-generation Americans feel deeply. It is not just about succeeding alone, anymore, it is making sure that everything you do is laying the foundation for a successful future.

“You’re not just improving your life when you work or study, you’re improving the country, you’re sharing your skill, and you’re a small piece of the puzzle.”

#CELEBRATE IMMIGRANTS

We all know someone with an immigration experience or have an immigrant heritage story of our own. Join us to stay updated as we #CelebrateImmigrants across the country!