Rachel Podber

Family history and traditions are passed down for generations — oftentimes, with one family member remembering parts of one story and others filling in the blanks. Our traditions are what make us feel at home; they can provide routine, like turkey on Thanksgiving Day; they can give us security and joy for our favorite foods with our favorite people; and they get shared with anyone joining our family. Rachel Podber became a part of her Atlanta-based family after being adopted at birth. Her whole life has been love and food from her family’s Polish roots, traditions from her family’s Jewish faith, and stories of her Zaydie (grandfather) and Bubbie (grandmother) who survived the Holocaust. For Rachel, these stories shaped her every move and has led her to a life of compassion and justice for all.

Rachel and her grandparents, Zaydie and Bubbie

Coming into a Jewish family and being converted as a baby, the rabbi who brought her into the faith made Rachel’s mom promise that she would continue her education and send her to Jewish day school. Her K through 12 experience consisted of just that — half the day in English, half the day in Hebrew. “I was very much in a Jewish bubble. I remember making a friend when I was 16 that was Catholic and I was like, ‘MOM, I JUST MET A CATHOLIC.’ It was very exciting.”

While Atlanta is a hub city with Southern flavors and international flair, Rachel wanted to pop her bubble — “my high school graduating class was like 52 kids, and pretty much all white Jews.” When looking at schools, Zaydie pleaded with Rachel to stay closer to home. But she attended Boston University in hopes to broaden her world view, meet others from around the world, and of course, set out to meet the now-late and great legend, Professor Elie Wiesel — and Zaydie couldn’t have been happier to hear. As a Professor Emeritus at BU, this Nobel Peace Prize winner’s Holocaust story “Night” has affected millions around the world. So on a chilly night in mid-November, Mr. Wiesel gave his yearly trio of lectures of his story, wisdom, and strong connection to Judaism. For Rachel, she’d heard her grandparents’ stories her whole life, but to hear from this global activist himself was especially impactful.

“Zaydie passed away in October of my freshman year, but [in] one of the last really coherent conversations I had with him, he asked if I had met Elie Wiesel yet and I said ‘no not yet, Zaydie’. We met Elie Wiesel and heard him speak about a week after I got back to Boston from his funeral.”

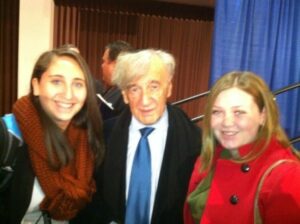

Rachel and Mariana (author) meeting Elie Wiesel

It was Elie Wiesel’s last year and lecture at Boston University. Determined to meet him that night and fulfill her Zaydie’s dream, she arrived early, sat close, and jumped for the stage with tears in her eyes when he finished. In the end, she shook his hand, got a picture and was able to briefly share her grandfather’s story where it all began on Sept. 9, 1919 in Vishnyeva, Poland (now Belarus).

When the Nazis invaded Poland, they forced all the Jewish people in every town into ghettos and decimated Zaydie’s hometown. Ghettos were enclosed and cramped and restrictive — what once housed one family now forced four together. They lived under miserable conditions with strict food rationing controlled by the Germans. But the determined 16-year-old Zaydie would sneak out to get bread for his family and neighbors. He risked death by the Einsatzgruppen, a mobile Nazi killing unit, with his bread runs. On one night, they took a group of men into the woods — Zaydie included.

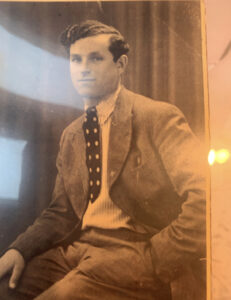

Rachel’s grandfather Zaydie

“My grandfather was one of the men they were going to kill. They started shooting everyone into a ditch. But there were a certain number of men on the side that were digging the ditch and my grandfather saw a shovel sticking out of the ground. So he grabbed it and started digging. [His fellow men] were like, ‘don’t do that, if there’s not the same number here when we end, as when we started, they’re going to kill all of us too. But he just kept his head down and started digging. So he always said that shovel saved his life.”

Though when the men with shovels returned to town, they smelled fire and smoke. While in the woods, the rest of the Jewish townspeople were forced into the synagogue where doors were locked and it was set on fire. Zaydie lost almost his entire family. After that, he ended up in his first concentration camp, Stutthof and later transferred to the sub camp of Kaufering in the infamous Dachau. In 1945, Americans liberated the camp and Zaydie, thankful and grateful, went to work in the Displaced Persons Camp’s kitchen peeling potatoes. Zaydie never met a potato he didn’t like. “He loved potatoes until the day he died. Like, that’s what he would order at every restaurant we went to; a baked potato, well done.”

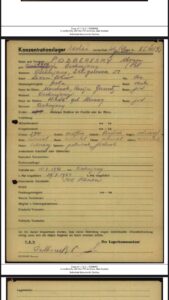

Rachel’s grandfather’s registration form when he was taken in Dachau

It was at that camp in Ulm, Germany where he met Rachel’s grandmother, Bubbie, where she had arrived after her and her family walked to the Russian border, were sent to Siberia, and then worked in a shoe factory. After 6 months, Zaydie and Bubbie got married in the camp, and thanks to the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee who sponsored Jewish refugees to resettle, they were able to begin a life in Atlanta. When they arrived, they spoke no English, just Yiddish. But as immigrants do, they persevered, opened up a grocery store, and eventually learned the language simply by interacting with their customers.

But sometimes talking to others, especially about his story, was too difficult for Zaydie. In 1993, when “Schindler’s List” came out and received international acclaim, director Steven Spielberg was compelled to start the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation, whose aim is to record testimonies of survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust. Zaydie was supposed to be interviewed, but “he had a big breakdown and it was too hard for him to tell that story. It wasn’t until he was older and had grandchildren, who were the light of his life, where he was like, ‘I need to tell them what happened, I need to make sure this doesn’t happen to them.’”

Rachel’s gradparents Zaddie and Bubbie when they got married at the Displaced Person’s Camp in Ulm, Germany

Rachel’s entire family seems to, in one way or another — whether it be the food they bring at family gatherings or chosen career paths — honor their history in some way. Her mother is a docent at the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum in Atlanta, educating visitors about the truth of the Holocaust, while Rachel is a docent at the Holocaust Museum in Los Angeles. “My mom said that she’s found once the survivors tell their story, they kind of can’t stop and it becomes a driving force and mission for them. I think once Zaydie was able to tell the whole story, once he realized how important it was, he started to see that.”

With the pandemic, Rachel’s new job as a docent was put on hold for months. However, today, she hosts virtual tours and weaves her grandfather’s story through the tour wherever she can. After every school group tour, a Holocaust survivor jumps on the call and students can ask questions from history itself. After a 135-student Zoom tour last week, Rachel knows this is an invaluable experience not just for the children, but for herself, who was so used to hearing these stories. “To see students from families with no ties directly to the Holocaust and seeing them meet a Holocaust survivor and hear their story for the first time and just seeing the impact that it had on them, has been pretty incredible.”

While the Podber family is used to large family gatherings for big Jewish holidays, they’ve resorted to Zoom dinners to celebrate their faith and food. When Zaydie was around, he would go to synagogue at 6 AM everyday, “which I always found striking that after everything he went through, he still had such a strong belief in God.” But it was his faith that gave him hope. And so it is that faith that the entire family continues to rejoice in.

“During quarantine, my brother’s girlfriend started setting up weekly Zoom calls on Friday nights to light the candles with her family” — and though Rachel is already fluent in Hebrew, she also joined her dad’s Yiddish Zoom class. “I’m slowly picking up more and more, but it’s been incredible to be able to briefly converse with my Bubbie. I made a joke to her in Yiddish and she understood.”

Some pies Rachel baked for Bakers Against Racism

So while Rachel is a third generation immigrant, she holds her culture and family close to her heart. Part of that culture is the food. For Rachel, Passover wins as the best holiday because of the togetherness. And the food. Did we mention the food? Food like Mandel bread, which, according to Rachel, no one makes better than her Bubbie. Or food like kreplach, matzo balls, sambusak, and kugels. And even the challah bread she makes for herself. Upon first moving to Los Angeles, she worked at an Israeli bakery. Rachel continued her love of baking when she joined Bakers Against Racism in June.

Organized by Chefs Paola Velez, Willa Pelini, and Rob Rubba, this worldwide bake sale used their fundraising to give back to fighting racial injustice in the United States, a historical nod to the early Civil Rights Movements that were funded by bake sales. Every baker could choose where to donate their funds, so Rachel split her donations between the Southern Poverty Law Center — which left a lasting impact on her from a visit when she was 15 — and the American Civil Liberties Union. After raising a total of $600, adding to the collective total of $1,859,234.08, Rachel didn’t stop there. Recently, she’s been baking pies for friends and family in the LA area, gearing up for Thanksgiving. Not only is she fighting in her own community, she is also thinking of her roots in Atlanta. “With the upcoming run-off election in my home state of Georgia, I wanted to help in some way, so I started offering pies, with a portion going to the ACLU and Fair Fight, the group founded by Stacey Abrams.” She will continue her baking in the next bake sale, “Bake the Holidays Better,” while she virtually attends the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom and pursues her Masters in Museum Studies.

Rachel’s grandparents, Bubbie and Zaydie

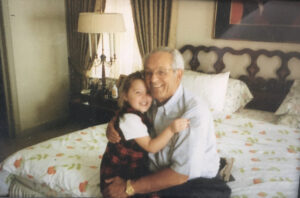

So, for this year — in a year of change and despair for many, joy and light in others’— Rachel thinks of her blessing of a family, the journey that brought them here, and carrying on the traditions that complete her. “One of the last things Zaydie said was that his only regret is that he won’t be at his grandkids’ wedding. But we saved his Talit (Jewish prayer shawl) to be the chuppah for each of his grandkids.” If it was faith that saved her Zaydie’s life and let him build anew in the United States, then it is hope that emboldens immigrants and all others to persevere. Let us hope, this holiday season, that we find strength for ourselves, our families, and our futures. There are stories to tell, things to learn, and history to be made.

Rachel’s favorite picture of her and her Zaydie

#CELEBRATE IMMIGRANTS

We all know someone with an immigration experience or have an immigrant heritage story of our own. Join us to stay updated as we #CelebrateImmigrants across the country!